Shanti woke up on the wrong side of the bed. She had a throbbing headache. When she went to the temple at 4 am, the temple doors were shut. Usually the priest would be there performing ablutions. Today, he must have overslept.

She couldn’t find any of the flowers that she needed to do her ritual pooja at home. So today her deity would have to make do with marigold. She hummed her prayers, prayers that she had learnt at her husband’s home. They were protracted hymns that she didn’t think she could utter until her sister-in-law insisted that she had to.

So the impossible became possible and turned into a simple habit. Long Sanskrit jargon became the everyday norm. She could even mutter the hymns and praises to God about the Almighty’s infinite beauty, beatitude, compassion and omnipotence. Now Shanti revelled in her poojas; they were her helpline to God.

The milkman came while she was praying. He was unusually early. The sight of him put her off. Siva was an unkempt leery-eyed fellow and his hands were ridiculously ugly. Shanti held out a pot to him as he poured the milk.

“What’s wrong with the milk today? It’s watery,” she asked trying not to look at his fingers.

“What are you suggesting?”

“I am suggesting that it is watery.”

“You think I would like to fool my customers at 5 am.”

“What does time have to do with it?” Shanti hated it when Siva was in a defensive mood. That was when he was usually in the wrong.

Shanti shut the teak door and heard him muttering curses as his bare feet crunched the gravel path. The gate clicked and he was gone. How everyone had changed after Ramu, her husband, had died. Her servants had become more demanding while her relatives were kinder to her. “Come stay with us,” they would say. Since she was childless, they hoped she could take care of their house when they had to go on a trip.

She had no reason to say no, so she went to relatives whom she usually met only at weddings. She had become like a pilgrim. After Ramu died, she began to do things alone. She went to the bank, bought her vegetables from the local vendor, trudged to the post office and once went by bus all the way to the city just to be a part of the big fair – the loud exhibition filled with trivia- parrots who predicted the future, popcorn vending machines, earthen pottery and large cane baskets – that Ramu would never take her to.

The freedom that someone’s death offered was tremendous; she was guilty in a way. She no longer took her former sister-in-law’s comments seriously. She felt like a bird free from all bondage and made up for her happiness by feeling bad about the insolence of her servants and the rudeness of the likes of Siva. Nothing is the same without a man in the house, she concluded.

The first page Shanti searched for in the newspaper every day was the obituary. She looked for faces she knew, almost hoped that she would see someone there so that the day would offer her something to contemplate about. Because death was like that. It made you serious and pensive. For a while, existence took on a different meaning and after that, the maya of life beckoned.

She had never thought that she would get over Ramu’s death. It was so sudden. But here she was sipping her tea. Disappointed and relieved that today was another death-free day. It was 8 am already and Maniamma hadn’t come.

Shanti hobbled to the kitchen. She noticed how her joints ached much more when her servants decided to take the day off. There were a dozen pots accumulated in the black kitchen sink. How frequently these women took the day off… and what could you tell them the following day. If you cursed, they would probably leave, and if you were polite they would do the same thing the following week.

She thought of her niece who was abroad. What a dreadful place! She had seen the pictures. A white desert and no domestic servants either. Her niece never let anyone know how difficult things were but Shanti could tell how happy she was when she came on the great Indian vacation and watched through the corner of her eye when the servant cleaned up.

“Aren’t you coming for the temple festival today?”she heard a familiar voice at the door.

Radha was her senior and she got along best with Shanti. They had nothing in common. Radha knew the Bhagvatam, a holy scripture, by heart. When Shanti was with her, she felt that maybe for a moment, at least, she could be a part of something larger than her monotone existence.

Nothing spectacular had ever happened to Radha. She was of average intelligence. She didn’t have the kind of face you would remember. Her thoughts were mundane – usually to do with routine. Her life with her husband was business as usual. He was a stickler for food and so she always had to spend more and more time in the kitchen patronising his appetite and that of his friends.

Shanti had forgotten completely about the festival and was in a dilemma. “Look at this pot load of mess that I have to clean up. Today I am the maid.”

“Come on, Shanti. Don’t miss the drum festival, plus there is dinner on the house, so you don’t have to get worked up about it.”

Ramu would never miss melam, as the drum festival was called. He told her that his heart beat like the drums during the festival. When she heard the maddening droll of the asuravadya, she completely agreed. Her knowledge of music was unrefined. She preferred the boatman’s singing to the relentless drums that didn’t stop till they bored a drill through your brain.

But she loved the finery of it all. People dressed in their best to witness the spectacle. Old women losing themselves like young inebriated music lovers. Everyone immersed themselves into the music as she observed the temple field, the giant pachyderms draped in god’s finery and the enormous torches illuminating the electricity deprived hours.

A free dinner was always a good thing. No washing up. No keeping leftovers back into the fridge. Yes, she would go. She dressed up in an ordinary inconspicuous mundu, the kind that widows wore, and later in the day after a light lunch of rice and lentils, a short nap and biscuits dipped in tea, she hurried to Radha’s humble abode. Radha was ready with her pack of grandchildren and they all set off to the temple.

They prayed there and waited for nightfall. Dinner was served and Shanti complained over a piece of papad that the milk she was being sold had become very watery indeed. She sat cross-legged on the floor with Radha by her side. “Papad?” Siva asked in a strange railway vendor voice as he served. Shanti continued eating, troubled by her unnecessary complaints. Why did these things bother her so much and why did Siva appear there at that moment?

Come night and everyone stopped observing each other and focussed on the eight elephants who stood before the flames. The drummers began slowly as though teasing their drums and the audience. Some bats flew over the temple roof. Shanti left Radha and her brood and went to light the temple lamps that had begun to die out with the night. Away from the crowd and the palpitating drums,

she felt peaceful.

She pulled the cotton threads back into their oily abode and silenced the unruly flames. She thought of the simplicity of the moment – the flame and her. Then she heard a shuffle of footsteps perambulating past. “Vishnu is a bit restless today.”

Vishnu was not the centre stage elephant and Shanti felt he resented this fact. Only the elephant with the perfect dimensions could make it to the centre of the pack and carry the deity. Shanti fed bananas to Vishnu every morning when she did her temple rounds. Today, of course, she couldn’t as the temple was shut.

She went back to the clearing where the drums were beating faster and faster. She stood by a lone pillar and then noticed that Siva was there. He hadn’t noticed her at all, she thought.

Vishnu was beginning to act strangely. He nodded his head and trunk severely and as though struck by lightening, she saw the crowd disperse in every direction.

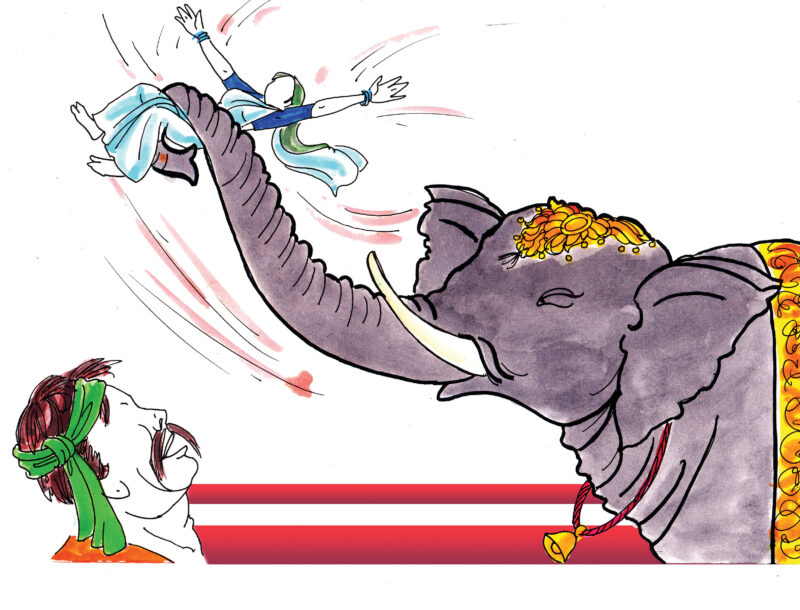

The elephant had broken its chains and had hurled the mahout in a circular motion.

Siva was transfixed with fear. He saw the elephant rushing toward him and reached out in a fit of fear to Shanti, pushing her before the running animal. Vishnu pulled up Shanti with his trunk and then flung her down as Siva watched the temple floor turn into a pool of blood.

When Shanti flew into the night sky, she had a final spectacular view of the temple lights and the people running. She saw Radha, she saw the milk man who pushed her, she saw her perpetrator, the elephant she had fed all her life. And in a split second, she recognised how extraordinary her death would be.

Siva never sold milk again. He didn’t know how his resentment had gnawed to the centre of his being and turned to crime. In a blinding moment when the elephant charged, he remembered Ramu’s mockery. Every morning he would tell him, “You stink,” or “Have you come straight from the cow shed?”

Shanti would look half mockingly when her husband gave out a gruff belly-shaking laugh as Siva walked down the lane, angrily banging the gate. He never knew then that his anger would fester deep within for so long and manifest in such a way that one day he would seek revenge. After all, such is destiny.

Neelima Vinod